We began with a fiction workshop on revision from Corinna Vallianatos. She began with her top ten on revision, with the #1 position comprised of suggestions from the class:

10. Put your classmates’ response letters away. Read them, but don’t keep them handy.

9. Be impatient. Be impatient with your own preciousness. Revision is like waking up with a hangover. You need to have the cold clear gaze of the morning after when looking at your work.

8. Be deliberate. Try to determine exactly what’s supposed to happen in the scene and what it’s supposed to do so it does something unique for the story.

7. Secure the point of view. Make sure that POV changes are done with intentionality.

6. Sharpen description. Whenever we go to a new place, spend at least one or two sentences describing the place. Keep describing, keep showing, never let up on the showing. Describe everyone in your story, no matter how briefly. Give everyone at least one sentence of description, ideally before they start speaking. Avoid generic description. Show what’s unique or distinctive about a character. Description is a conduit for depicting character.

5. Tighten and sharpen language. Choose an arbitrary goal to trim x words from a story to remove needless words: direction words, redundancies. “he nodded his head” to “he nodded”. If the adverb doesn’t enlarge the verb then get rid of it. Make verbs as active as possible, nouns as specific and precice as possible. Pick a tense, stay in the tense.

4. Be aware of your own tendencies. Know your work better than anyone else. Watch for the unusual words or sentence constructions, crutch descriptions. Vary sentence structures and word choice.

3. Dialogue. Dialogue needs to move the story forward and/or characterize. Look for places where dialogue can be sharpened or excised.

2. Read it out loud. Nothing makes problems more obvious than reading it out loud. It can be interesting to hear your words in someone else’s mouth. “Computer can read it out loud for you if you don’t have a friend” —Steven Paul Lansky

1. Suggestions from class: Know when to stop • Have no bias • Be willing to retype the whole work • Keep your original draft • Remember the small details • Cut up the chapter or story and then rearrange to re-envision the work • Let the text rest • Let a trusted reader comment on it

This was followed by a writing exercise on writing beyond the story:

Have the main character of the story you’re thinking of do the following exercises—as if he/she has his/her own notebook. Try, as much as your sense of decorum allows, to pretend that your character is writing the following, not you:

• Write a diary entry for the time of the story

• Write a diary entry for the time preceding the story

• Write a letter to someone who isn’t in the story about what’s happening in the story

• Write a letter to someone in the story.

Or you might explore places in the story that you haven’t either dramatized or summarized:

• What events happened before the beginning of the story? Before page one? Try writing a scene that comes before the first scene in your story.

• Write past the ending. Write an additional page past where you felt the story’s end was. This allows you (the writer) to understand the ramifications of the events that have already happened.

The rest of the morning was a mentee workshop then after lunch we had the last of the student seminars. I had Resa Albohor writing about leaving the stream of consciousness without drowning and Dan Cox on teaching creative writing in prisons.

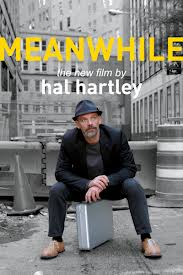

Our evening “reading” was a screening of Hal Hartley’s Meanwhile followed by a question and answer session. The star of the film, D. J. Mendel bears a striking resemblance to our own Cully Perlman. He does at least now have an alternative nickname to “Heisenberg.”

Leave a Reply